Measuring water risk requires multidimensional, geospatial data which is a combination of hydrogeological, socio-cultural, administrative and economic indicators and collected at an adequate temporal frequency. At present, in India, this data is not collected at a resolution high enough to be meaningful for micro-level planning of water conservation initiatives, or to be able to truly understand the extent of water risk faced in India today.

In this study, the Sattva Knowledge Institute (SKI) describes

(1) the role water data plays in corporate water stewardship planning;

(2) the available open water data platforms in India, as well as their spatial resolution and temporal range;

(3) challenges with the accuracy and availability of water data in existing sources and

(4) citizen science initiatives underway in India to improve access to high resolution and accurate data.

Through our research, we found that:

- Due to the absence of real time and accurate water data at a micro-watershed level, corporations in India often spend a large amount of their water conservation budget towards “source vulnerability assessments” to identify the water risk hotspots near their factories or plant locations.

- These one-time investments on collection of water risk data are typically not open for public consumption, hence, the investments are not leading to long-term improvement in understanding of water risk at a basin level for a range of actors that can potentially solve for it.

- These assessments are also not repeated at a regular frequency, or standardized in their forms of collection, making it difficult for corporations and the country as a whole to know the progress made through various interventions, such as construction of farm ponds, check dams, or even water-use efficiency programmes in agriculture.

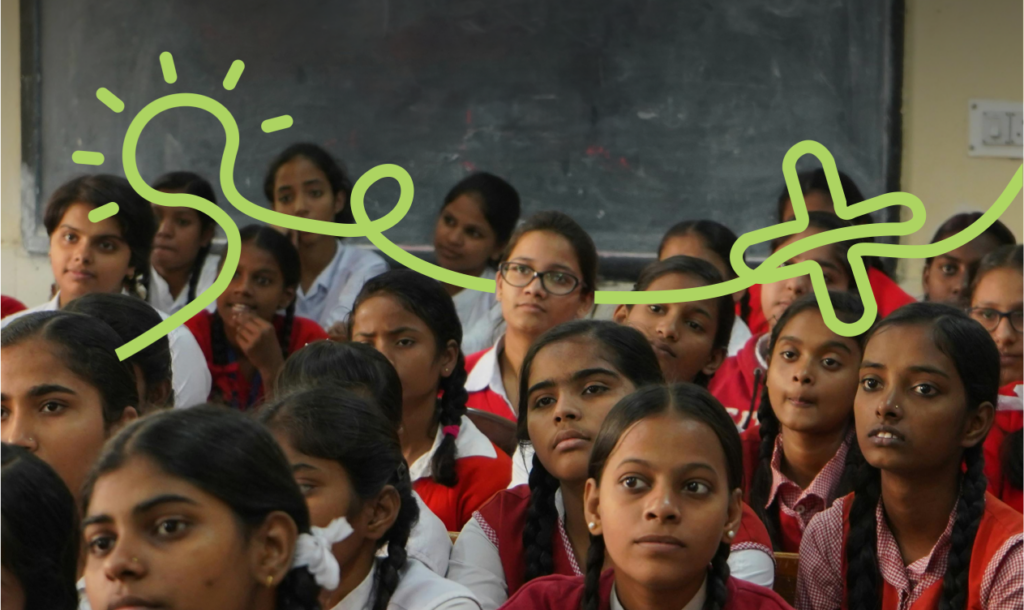

- To resolve this, several academics and donors are exploring the possibility of citizen science, where community members can be trained to input data on water risk in their locations and mitigate the accuracy challenges from the secondary sources.

Through these learnings, SKI concludes that there is a strong need to map the “top-down” (through satellite imagery, remote sensing and large data collection programmes) with the “bottom-up” (e.g. community sourced) water data to be able to appropriately monitor and collectively act to resolve the water crisis in India.

Acknowledgements

Authors: Vanya Mehta, Rathish Balakrishnan, Debaranjan Pujahari, Kangkanika Neog

Contributors and Reviewers: Anantha Narayan, Aayushi Baloni, Aman Singh