As per the Annual Status of Education Report or ASER 2022, in India the enrolment rate for primary schools stands at the highest it has ever been in Indian education history at 98.4%. However, only 42.8% of grade five students are able to read at grade level text.

Assessments of foundational literacy and numeracy (FLN) outcomes have been thrust to the forefront of understanding what the problems in education are today, so that they can be solved more effectively. So how can we decentralise education solutions? Can we get closer to the context rather than put a one-size-fits-all model? How do we evoke constructive action from different parts of the community? And can we create more owners who own the problem of improving foundational literacy and numeracy, than just a few people sitting in Delhi?

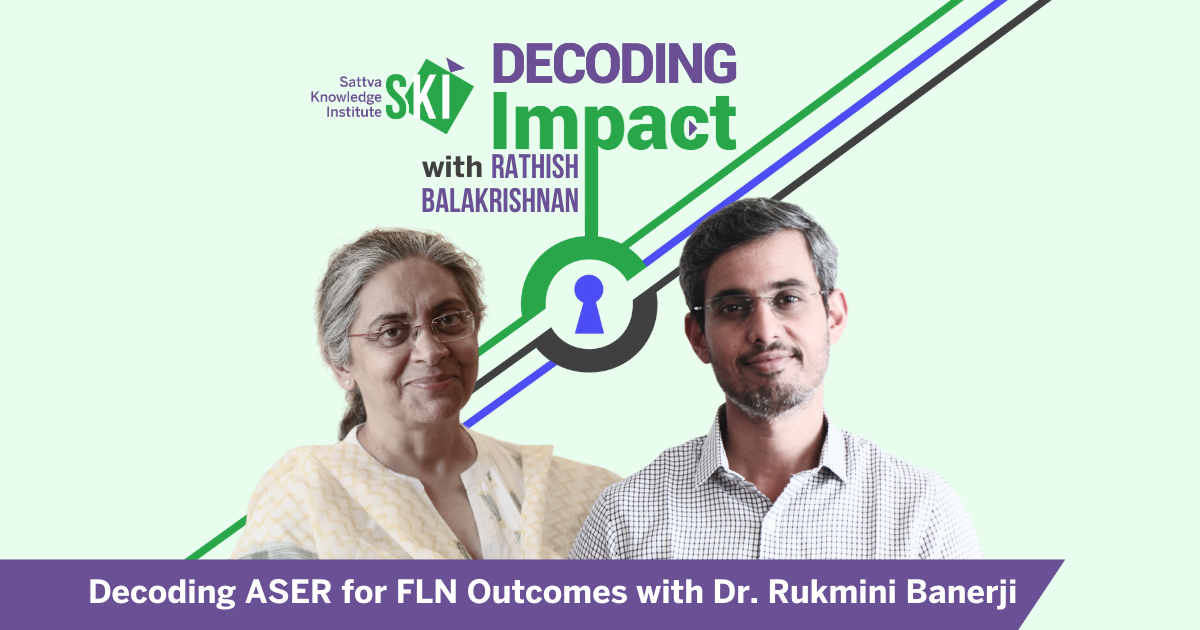

To discuss this and more on Decoding Impact, host Rathish Balakrishnan caught up with Dr Rukmini Banerji, CEO of the Pratham Education Foundation which facilitates the ASER survey.

Episode Transcript

Intro: [00:00:04] You are listening to Decoding Impact, a podcast by Sattva Knowledge Institute hosted by Rathish Balakrishnan.

Welcome to season two of Decoding Impact. Every fortnight we will engage leading thinkers and practitioners to understand what it takes to solve systemic problems at scale. For all the curious changemakers committed to understanding the trade-offs and incentives to make this world a better place, this one’s for you.

Rathish: [00:00:51] Education is often considered the Harry Potter of the social sector. Every philanthropist can recognise and relate to the value of education in improving lives. But despite significant investments, the quality of education continues to remain poor year on year. Part of the reason for the same is the way we approach the challenge. It is often easy to think of education as a technocratic problem by looking at how concepts like fractions are more difficult for a child than decimal addition, for instance. But the true attention in education today requires us to approach it as a social problem. It’s about ensuring that every member of society takes accountability for good learning outcomes. The Annual Status of Education Report, otherwise known as ASER, sets a definitive standard for reporting the quality of learning outcomes in India. Over the years, ASER has highlighted the increased awareness about the need for education among parents and contrasted that with the poor quality of education in this country. While everyone knows the oft-quoted statistic of the grade five child not reading the grade two texts, I truly believe that ASER is a social movement structured as a survey. So how does it start and how has it evolved? What can the results over the years tell us and what does it take to make another ASER happen? To answer these questions and more, we are joined by Dr Rukmini Banerji, who has spent decades thinking about this problem. Dr Banerji is an accomplished educationist and the CEO of Pratham Education Foundation, India’s leading NGO, focussed on improving the quality of education. She is an advocate for data-driven education reforms and has spearheaded the development of notable large-scale assessments, including the widely recognised ASER. Welcome to Decoding Impact. Dr Banerji, great having you with us for today’s podcast.

Rukmini: [00:02:41] Good to be here.

Rathish: [00:02:57] Ma’am, I have been probably in a dozen meetings where people have said we should start the next ASER, you know, and we should do the ASER for gender, we should do ASER for secondary education, etc. And for me, that is a sign of the impact that the report has had on education and more largely the social impact landscape as probably being a cornerstone of what civil society has brought together as data and evidence that has influenced the entire sector. And today’s conversation, ma’am, wanted to not only talk about the 2022 report, which definitely would like to touch upon but really look at the evolution of ASER, because ASER, as we know it today, is not the ASER that started. And so throughout today’s conversation, I thought we could divide it into three parts. One, of course, is to talk about evolution, what has worked? Why is it where it is today? Two, speak about the 2022 report itself. What are some of the key observations and insights? But also end with looking forward at a national level, where are we going with this conversation around learning outcomes at the foundational level as well? But let’s begin at the beginning. It will be great to hear from you the story of how did ASER start and what were the initial ideas and how has it evolved over the years?

Rukmini: [00:04:15] Uh, it’s great. You know, the older you get, the longer back you can go to tell stories. So see, a lot of people think ASER started as a national assessment, and that’s absolutely not the case. We were working, you know, now, let’s see, almost 23-24 years ago. After our first couple of years, which was largely in Bombay, a lot of our own focus was on how to increase schooling either from how kids can get into school. So if you had a universal first standard, then you would have a universal primary. So how do you get that transition to happen well? And also, how do you get children who are, you know, who had been left out either because parents had moved to Bombay or they never had a chance? So how do you get the left-out children to come in? So we did a modification of the famous foundations bridge courses, but for an urban setting and so on, so largely preoccupied with how do you connect children to schooling. But as we were doing that, I think there was a sense in which the visible problem, which is children out of school, was getting solved and there was a common understanding around that. But along with that, there was a restlessness and a kind of a little bit more fuzzy thought that the children who were already in weren’t doing quite like you would want them to do.

Rukmini: [00:05:32] Teachers felt that they were not able to really transact the kinds of things that they were expected to do in class. And parents felt that children weren’t gaining the value add that they should. So, you know, the left out problem, let’s say, was very clear, but the left behind problem was being felt, I would say, and we could feel that as well. We worked both in the community as well as in the schools in Mumbai at the time. And so it seemed necessary to kind of put some form or shape or understanding around that. My own belief is that because the left-out problem was clearly understood, you know, there could be a very wide spectrum of people, parents, policymakers, administrators, etcetera, to come together to solve it. So to solve any problem, you need to sort of see the problem, and articulate the problem that can then be addressed. So in our own work, we slowly began to see that perhaps the place to begin that was holding things up was if you couldn’t read, you couldn’t really do much else. You also had difficulty in math. So basic reading and basic math seemed to be prerequisites for moving ahead. But what do you mean by reading? I mean people think of reading in many different ways.

Rukmini: [00:06:46] There are textbooks, there are other books. There are all kinds of things. We had been working in the Bombay Municipal Schools in a program called Bal Sakhi at the time, which was providing kind of a learning support to the children who were what at that time was called lagging behind. And we were doing that not just in Bombay but in several other cities. And the first randomised controlled trial that J-pal did with us, I’ve almost a feeling that they did it before they were even called J-pal to look at the effectiveness of this program learning support program in Baroda and in Bombay. And during the course of that we realised that while we were working hard and children were making progress, the way we were assessing the children because, you know, like a normal test, a pen and paper test wasn’t quite giving us what we wanted. And the second is, even with the tracking of children’s progress that we could see, there certainly was progress, but it wasn’t at the level at which children needed to be if they wanted to really be on par at grade level. So a combination of these things led us to say, let’s just do a control-alt-delete. Don’t know. These days, nobody uses those. Don’t know what you do to your computer when it crashes. But in those days at least you did a control-alt-delete and said, Let’s just start again because we were frustrated that we were also kind of missing something somewhere.

Rukmini: [00:08:03] And so a bunch of people in Pratham, you know, I think close to about 100 or more started with Fresh. And there was a combination of in-school children as well as out-of-school children, with different languages. And we thought, let us try a month. Why a month? Just because a month is a useful unit of time. What if 100 people, 100 or more people are doing these groups of children, we need some common vocabulary to talk to each other to say how do we articulate what we are doing? So the idea was, let’s just look at where the children are today. And all these children we had decided were a little bit older, eight or older, plus three or older, and let’s decide on where we want them to be. So where we wanted them to be was very clear. They should be able to read a simple story and be able to engage with it, you know, read it, talk about it potentially, you know, criticise it if necessary, but then work backwards, what are the steps? And so the first step was clear that you can’t even recognise any letters. The next step was you can recognise letters, but you can’t read words.

The third step was you can read words, but you still can’t deal with sentences. And so that’s how these 4 or 5 steps emerged. We didn’t move to a single sentence because we could see the work that we were doing with the kids. There are a set of simple connected sentences, actually a lot easier to read than one single sentence because kids get the hang of what it is about and then they can do a little bit of guesswork and a little bit of decoding to put things together. So this now what is called the ASER tool, actually emerged as a way of having a, you know, a frame within which you could talk to each other so that I could say that. Rathish, in your class, you had some, you know, ten kids at beginner and five kids at para and six kids at, you know, word. And in my class, everybody is either a beginner or a letter. So our starting positions were different, but our goal was the same. We wanted at the end of this one month or whatever time period to have children reading a story with understanding. And that’s how it started. And that’s what held this whole experiment together. And we saw two things. One is that you know, children did make progress because we put aside everything else, our own preconceptions, and started at the level at which they were.

Rukmini: [00:10:15] And you can see that years later now, that whole approach is called teaching at the right level. According to us, there is no other level to teach at. You must teach at the level of the child. But there were some things that happened that we didn’t expect. So this little ladder or little frame was for our own internal conversation. But that’s how we went and began to talk to the parents or in some cases when it was in school to the teachers. And 2 or 3 things came out of that that we hadn’t thought of. One was from parents who say, What are you doing exactly? So we’d say, we are trying to take your child from wherever the child is now to the story level and the story, even if parents couldn’t read if you read out the story, it was very obvious What a story, right? So the goal of the entire exercise was visible from the simple assessment tasks that we were doing. And the way to measure progress was also inbuilt because, you know, you move from letter to word, from word to para, from para to story. You could see how long it took them to make these jumps. And interestingly, all the materials we use were like that. You played word games, you played alphabet games for easy reading.

Rukmini: [00:11:21] You had the little booklets for four lines, and then you had stories. So really, the distinction between assessment and activities wasn’t there because this was all part of the same game, and you were also able to connect to people outside to say what it is that you are doing, bring people onto this journey so they could follow your, you know, along with it as well. Now, as we were doing this and the logic of this assessment, the activity and the action sort of came together was also a time when we began to work in rural areas. At that time, largely everybody in Pratham had an urban background. And so when you moved in, we could see that our own urban backgrounds were quite different. For example, I’m from Patna and had worked in Bombay, so the Bombay setting and the Patna setting were quite different in terms of children, their composition, and their starting level. But as we moved into rural areas, it was important that we first understand what is the current context. So we began to use this simple tool. We had a similar one for math as well, to do what we were calling village report cards. So you arrived in a village. The village is often too big, so you look at Hamlet by Hamlet and you do this little one-on-one exercise with each child.

Rukmini: [00:12:34] And as soon as you began to do it in the community, a lot of people would say, What are you doing? Then you would explain them. They’d say, Oh, okay, I can help you. And so in a period of 2 or 3 days, along with a lot of help from the village, you were able to produce a village report card, which was really a census of schooling and basic learning in the village. And then you would have a meeting, you know, in the school or in the Panchayat Bhavan or wherever, where the whole village would come, where you would discuss this village report card and think about what should be done next. And, you know, as you can imagine, a ton of stories around this, but the logic actually, it moved from our own assessment activity, action and that whole circle to a village level where that began to happen because the village then gave volunteers to help to take this circle further. And at that point, you know, the government was a new government in place talking about not just outlays, but outcomes. Madhav, one of our founders, was in the National Advisory Council, where I suppose some of this discussion happened. And so the idea that could this, whatever you call it, this circle of action be done at a national level because it seemed very important as it was with us or with the village, you need to understand the problem.

Rukmini: [00:13:50] You need to feel the problem, and then you need to be able to discuss the problem. And once you do that, there are a lot of solutions. So all this story, I would say, began around 2001, but it was only in 2005 after, you know, hundreds of village report cards sharing these kinds of methods, if you may, the tool and the method with other partners, governments or whatever, that we came to 2005. And there as well, I would say that the first year I don’t think we realised what we were getting into. And I always say that you have to be very careful what you name yourself because ASER seems to be a good word. It meant an impact in many Indian languages. But what we didn’t realise is that the word ‘A’ means Annual. So, you know, that’s kind of the beginning of us. It did, it did not start out even as an assessment tool, forget about as a big sample study of India or anything like that. It started as a way for us to understand our own challenges and have a way of talking to each other, which we then were able to, I think, quite successfully spread locally wherever this was going to happen. So that’s sort of the history of the beginnings of us.

Rathish: [00:15:16] I have a lot of questions, so I’m going to sort of place them one by one. You mentioned it’s 2001 to 2005. That was about 20 years ago. Today we are at a point where the conversation of learning outcomes seems like something everybody, you know, thinks is important, the government thinks is important for everybody there. We are also now saying, okay, what beyond learning outcomes? So there is that conversation that’s evolving. How was the scene then like when you made this study and then you said, Hey, learning outcomes are important? You did mention that the National Advisory Council was taking cognisance of it, but across states, given education is a state subject, was there this awareness that the problem is so huge or that the problem is so important for people to look at? And again, I always feel when you work on something for 20 years, you have the benefit of accrued value over the years. It’ll be great to see what was the scene then and how has it evolved in terms of the importance of the issue that is being discussed.

Rukmini: [00:16:10] So I would say that you know, the same year, 2005, the central at that point was called the Ministry of Human Resource Development and also commissioned an enrolment study. You know, what the enrolment patterns were, and that was an urban and rural study. It was rural, but the numbers from ASER for the rural districts matched very closely to the enrolment numbers that came from a third party, but also a household survey. So at one level, there was that credibility that the numbers that were coming out were not, you know, dramatically different. People had not thought about testing, learning or whatever in that way. Even at that time, it was early days of the National Achievement Survey that was done for the third upwards, and it was done as it is done today as well at a kind of a grade level or at a, you know, at a level which is not very basic level. You know, even then there was a third and a fifth and an eighth. And the idea was that you’re tracking progress across these very, very interesting sets of reactions. A couple of things about the architecture that we had probably, you know, because of the large number of experiences at the village level, I think some of our metrics and methods were bang on the spot. And often when you work things from the ground up, you tend to be more solid than if you just sat with statisticians and this.

Rukmini: [00:17:29] So right from the beginning, ASER was done by a local organisation in that district. So I think that was an important one. You had to find these local organisations. We had no money to give them other than maybe a little bit of money just to go to the village and come back. The sampling would use census lists. So that’s something that we still do and I think the simplicity of the tool really helped in both. And we knew that it helped us to understand things. It helped people at the village level to understand things, and it helped up and down the system. There was no mystery about what this assessment is. What you see is what you get. So these have been very key features, I think, in the way. And I think the final thing was that you know, I mean, although people may have interpreted it differently, it was really an effort to say, as a citizen of India, I have a role to play in the development of my country. And so if I understand, where are we with schooling and where are we with learning? And I’m a local person, so maybe I can contribute as well in, you know, taking this forward. We knew from other things that, you know, you do a district here and there, it doesn’t have that impact.

Rukmini: [00:18:40] So the idea was to do all of India at one time and do it in a way that would have a national and a state and a district all available at the same time. The timing was important. The agreement to us within Pratham remember, was October 2nd and it happened to be a holiday, but it happened to be a very significant holiday as well. You know, phone calls were made to all our state teams to say if we were going to go ahead and do this. What do you think? And, you know, everybody was 20 years younger and said, absolutely, do it immediately. So in the first year, we were able to reach 475 districts and the timing of this was fixed, that even though it was 2nd October, we would come out with this report before 26th January because people get preoccupied with 26th January, then the budget et cetera get formalised. So we wanted to have data for that year available in that year itself so that you could plan for the next year. I think these features also helped a lot. Now, in terms of your reactions from different states, why the difference? There was one state in which when the results were presented, it was almost like we thought people would come, you know, because the government people said, give us the names of every child and every village.

Rukmini: [00:20:01] This can’t be true. I remember a conversation in U.P. where the U.P., you know, secretary or whatever, state project director, whoever the senior person was, had the report in front of him and was talking to him and he picked up the phone and called his counterpart in Tamil Nadu. So I couldn’t hear what the Tamil Nadu guy was saying. But what this guy was saying was that you know, I can believe my results for U.P. because the enrolment numbers match pretty closely, but we’re learning, you know, you realise can be very poor. But Tamil Nadu, which has very high enrolment, how can it have these kinds of results for learning? So number one, and remembering this conversation very distinctly, he said, We are following the Tamil Nadu pathway. You’ve got your infrastructure in place, you’ve got your teachers, you’ve got your textbooks, and now learning will rise. But if that’s not the case, then who should I follow? And they ended the conversation by saying either these guys are completely wrong, pointing to me or we have something really major to worry about and I have to give credit to U.P. They actually embarked immediately on a conversation to say what to do next. What do you think looking at these results and can I talk about that a little bit later?

Rukmini: [00:21:15] Year on year doing it year on year. Also, we realised after a couple of years it was important because people changed their minds. The same government who had come to fisticuffs a couple of years later said we are doing an internal evaluation of our learning outcomes and will ASER come and verify that we are doing the right thing. So, you know, if it’s your own country and your own effort and you know you have no deadline in mind, then I think it gives lots of room for people to change their minds, to feel differently. I mean, once one standard thing and this is on a slightly lighter note, several state governments say this year, the results have been good, so let’s take a picture with you. And if next year, it isn’t that good, we will say that the sampling is wrong. That’s kind of like what should happen in a large joint family. If you disagree sometimes, sometimes you go to court on land and sometimes, you know, you intermarry. You know, all of these things are possible. So I would say that the understanding that this learning was very key happened over a period of time. And sometimes to me these days, it’s very surprising how people are just now, you know, it took ten years to accept and then there was always a division or people say, what did the government do? But there is no government. So at the central level, there was the Ministry of Human Resource Development, and there was the Finance Ministry. You know, they had different views on ASER because the finance ministry thought this leads to outcomes that are very important. It would feature us in the Economic Survey for many years. The Ministry of Human Resource Development naturally felt this was a bit of an attack on what they were doing. But at a personal level, I think nobody ignored us. You either liked it or you hated it. It was very difficult to be neutral. And the fact that predictably, year on year, it was always coming out in that middle of January, also I think established a certain, what shall I say, long run presence on something like this. People don’t, by the way, debate the results even today. Even that happens today. But we know that. See, I feel like something like the ASER report, whether at the village level with the report card or with the national level or state level, it’s an occasion to talk. I don’t have time at home. I don’t have my purse with me, I have the ASER tool in it. Every day, I don’t know what conversation I’m in, the tool comes out and it is featured in some parts of my conversation. So the opportunity to talk to anybody at the bus stop, in the auto, in the Planning Commission, in the NITI Aayog, in the state government. I mean, it’s a wonderful way to have something that you can talk about.

Rathish: [00:23:48] There’s one thing I wanted to ask you, which is, looking back, what has made it successful? And throughout many conversations, I have actually gleaned a few. So I want to share them so that you can build on top of it. A couple of things that you rightly said, which is simplicity, to actually have a tool which everybody can understand, I think is itself something that’s very, very relevant because I’ve been part of assessments that take 1.5 hours per child, so there’s no way you can do this at a national scale. The second is and is something Aditya Natraj from Kaivalya Education Foundation spoke to me multiple times about because I’m an engineer. So I always look at technocratic solutions and he always used to say ASER was a movement. And you talked about it as well. Everybody came and became a part of it. It wasn’t like three sorts of people, bureaucrats coming or doing conversations. It’s literally that the village sort of joined forces to be able to be part of that. So that movement approach to things where everybody sort of felt part of it in some form I think is important. The third thing that came up, you know, when I was talking to one of your colleagues also is that the results made sense for a parent, not in a way that you had to write a 25-page report, but in a way, the mother sees the child read.

Rathish: [00:24:56] The mother already knew the results, which made sense to her, and the father realised it made sense to her. That way the loop wasn’t closed at the highest level. It made a closed loop at every level, which I thought was very, very important. And for the kind of results you’ve had, no one questioned the rigour of ASER, and it’s very easy to take simple tools and say it’s too simple, so it must be wrong, you know. But while people might agree, disagree, etc, everyone said that this is a rigorous tool and people have replicated it and hence the focus on rigour and no sampling for you, the way you approach door to door, how you turn, etc. There’s a lot of rigour that goes into the design and execution as well. And finally, the fact that the numbers in the end, however much the survey is long, the result is a quotable result. The grade five child was great to text like every education, non-profit organisation, education, Start-Up starts with the ASER results saying Here is why I exist. Because this is the problem we are solving. For me, these are things I gleaned from many conversations. But when you look at it, what are some others that you would say have really contributed to the success of ASER?

Rukmini: [00:25:59] Success or failure? I don’t know. But the persistent presence, I think, is something that, you know, we are also sometimes sort of taken aback by that most things in 20 years you outgrow, you know, but this still seems to be relevant. But I think that often ASER is looked at as data. I like to think of it as an experience, an experience that connects you as an Indian to India. I don’t think we have enough of those, which brings the whole country together. So even starting from the first one, you know, for whom is this being done? It is being done for you and me and for my neighbours and everyone else. Right? I remember even in the village report card days, Sarpanch would say, you know, we tell the Sarpanch or the Pradhan, whatever, that we are going to go do this. And then when the actual piece of paper was done, the Sarpanch would say, Where should I sign? And I’d say, Nowhere. He said You don’t know because the data always goes up. It’s the only thing in the world that defies gravity, right? And we’d say, But the data has nowhere to go, this is for our use. So we never collect the data for us because it’s either one old lady in the village and I often thought about this story and it’s getting even more important now that my own hair is white. She was watching what we were doing in the village and she said to me, what are you doing? So you are going home-to-home, showing papers, what is going on?

Rukmini: [00:27:18] So I was in a hurry and I said we were doing a survey. So she started laughing. So then I stopped and said, Why are you laughing? She said surveys are something that you people don’t know and we have to tell you, you know, people come from cities and outside, they ask some questions, What is your income, where is your water, all that kind of stuff. And so we have to tell them but they don’t know it. But what you are doing here, this even we don’t know, you don’t know, together we’re finding this out. An illiterate elderly woman in the village who had just been observing us and she comes back to my mind that this is something that we are uncovering together if we don’t build a common understanding. And people debate. But I think that this uncovering together is and it’s not like we planned it like this, but I think in the doing of it, we’ve learned that uncovering together, debating together, that together part is very important. We have a society where certain parts are moving ahead more rapidly than others. This view of not just my child, but all the children in Hamlet, the Hamlet, the aggregate, you actually know all the individuals. By the time you get to a village level, it’s an aggregate so that, you know, what is the aggregate, what is the individual? Where am I in this aggregate? Do I have a role to play? And, you know, over and over again, I mean, ASER has been going on now, what, almost 20 years. Every ASER, no matter which district in the country you go to, I find that it’s usually young people, usually students and how many college students have never been anywhere. They’ve been to college, they’ve been to home, they’ve been to market, they’ve been to relatives’ homes. And this adventure that I will get the name of a village in my district, I’ve had people come. I remember, we were doing training once in a district in U.P. and I was staying there at night in the district, in the village, and there was a knock on the door late at night and two girls came who had been on the train. Very hesitantly they said, Ma’am, because you are a lady, can we speak to you? We are getting scared, how will we go tomorrow? So I said, Are you scared about getting there because of how there’s a bus or whatever it is? They said, no we will reach there. So we know how to go by bus and all but how to speak to strangers? So I said you go home. By the way, strangers are easier. Family members are much more tough. You go home, take the rudest person in your family and do the test. And they came back the next night and said full-day training wasn’t as useful as the input you gave last night because you know I want to go out. I want to see my district. I want to see my country. I have no idea. So many times, you know, in Kashmir or in the Northeast, kids will say, is India like this? Now, if this was an opportunity, instead of calling it ASER, we called it See India. My own belief is at a young age, if you participate in a productive experience. And if you do it together, I really feel a lot of our problems would be lower because you would respect them. You go into a village, it happens to me still. I get little butterflies in the morning. The same thing as those two girls like how to talk to strangers, will they talk to me and all that. By the end of the day, there are people who are saying, Have some tea at our home. Why are you going away? Stay the night, blah, blah, blah. This ‘Humdardi’, you know, this feeling of we are here for you, we are all pretty similar. These are very simple but powerful things. And so I think these are some of the things that underlie ASER. Today, like this year, the 2022 report was disseminated very widely. We made a big effort because after four years to do district-level dissemination, the number of district officials, whether the collector or the district education officer, who in their college days had done ASER, was phenomenally high because it’s that generational thing. So these are just my own favourite. And you know, everything is put up in its open. So we have no idea actually how many people use the ASER tool and we hope they use it as simply as we do and not complicated, but it’s not ours. It is there for anyone to use.

Rathish: [00:31:28] You know, these days we throw the word public good very loosely on very many things. Digital Public Goods, etc. But, ASER is truly a public good and is something that is created for and by the people. And I think that actually is a huge value. And I still find that remarkable.

Rukmini: [00:31:46] In 2022, we reached out a lot and I think I pressured a lot of people, my own family around September doesn’t take my phone calls and whatever. But, you know, again, it is a local level. Very often we’ve had petrol pump dealers say to get them petroleum or a printer will say let’s print. So, you know, and frankly, nobody funds it in money terms, but 30,000 people give their time. Monetising that would be huge, right?

Rathish: [00:32:16] I want to go to the 2022 result, but I want to say two things before I go. One, this idea of socially understanding what we are doing in educational interventions I feel is a losing art or a science. I don’t know if you feel that way. I think we are becoming a lot more technocratic about our interventions, but this ability to say, how do we bring everybody along? How do we get people to be part of the solution, I think is becoming, especially in education now, something that not many entrepreneurs who are coming in understand cognitively means, understand instinctively as well. And I think so as people are listening to this and I’m going to sort of push this to everybody I know say, how do we integrate this thinking? Because of this you know, I often talk about this idea that Gandhi Ji really made the Indian freedom struggle a participative movement, not because we needed the people, but because when people became part of the solution. So, you know, burn your clothes, take that salt, you know, do that thing because then you’re not listening to somebody sitting in Delhi telling you what independence is like, you’re recognised that it is independence, and that changes the way you look at how you see yourself as part of the solution.

Rukmini: [00:33:19] I mean, Gandhi Ji is not incidental, October 2 may have been a holiday in which we could have called people. We are very inspired by the simplicity of bringing people together. You know, while the education reforms and all of this is becoming more technocratic and dashboards and metrics and, you know, all kinds of things, this year I wanted to and hope whoever is listening will listen to this part more carefully. We took the ASER report and we looked at it and we know that the country is focusing in a big way on education departments, consulting companies, people who are in teaching, learning on the first three grades, you know, foundational literacy, numeracy. And my question also has been that that is absolutely necessary and needs to be done. But what about the other kids? Their learning levels were low before Covid. It fell a little bit during Covid. And what about them? Right. So in disseminating the ASER report, we often ask district-level people, institutions, officers, and whoever we met what we should do but didn’t leave it that open. We said one thing we feel, which is low-hanging fruit, is kids who are going from fifth to sixth. They lost two years. They gained one year. Last year was a continuous year. They may need a little push and they’re old enough that one month would have enough impact. Across the board, people said it was a good idea. Summer Vacations, one push. There is time during, you know, whether you are a government or non-government. So we picked three states, three Hindi-speaking states with results we looked at in ASER and we could see that this one push, even on our data, would take them to a level where they could maybe fuel themselves. And we appealed widely to say, if you are 10th or above, can you help 10-15 kids in your village? Today’s count in the U.P. is 1,10,000 volunteers. There is no money involved. Bihar is heading from yesterday’s number of 60 something thousand. Madhya Pradesh is 50-something thousand. And I think part of this is because part of this whole deal was that you also upload your you know, what you’re doing on the a portal, which may be taking more time. Even more interestingly, in two of these states, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, the government has come in full swing. So a government supporting a voluntary movement, I mean the government saying, do Jan Bhagedari, we can understand, but in both cases completely without those coming in place, the government saying can we use our resources to bring people on board. And in Bihar, and I’m not saying this only because I think Bihar is the best state in the world because I’m from there. The skill development mission has come on board. Jeevika, which is the big Rural Livelihoods mission, has come on board. The NCC has come on board. They have a Department of Mass Education which has what they call Tula Shiksha. I mean, anybody and everybody has come on board to say that we can do at least this much. And again, it’s the simplicity. One month, children going from fifth to sixth, they should not feel that they are weak, you know, it appeals to the goodness in you and 1.5 hours a day for one month, almost anybody can do. I think we don’t make these appeals enough. We make them complicated. We think people are things that have to go through some very complex convergence process. Some processes converge if they make sense, you know. So I’m very energised. In fact, one of the reasons we are doing the podcast today is for the next two weeks I’m going to be on the road because when you ask young people, Why are you doing this? And they often turn it down and say, why not put it on because you can do that much. If you reach ten, you reach success. So ten more kids, half of them are your cousins, helping them, why not? One more thing. I think people like being part of big things, but I’m not like some outstanding teacher who is doing my own thing. Like me, there are one lakh others in U.P. does give a, you know, feeling I’m part of something big, but I’m doing my own thing, you know?

Rathish: [00:37:17] I think, one, it is a significant report in the context of what has happened in the last few years, which is really one of the worst impacts that we have in education in terms of external disruption. And a lot of what we are seeing is explained as the impact of the pandemic, which it might be. There has been a significant loss in learning. Your number shows us that compared to even 2019, our numbers, you know, in the current report are worse. And two are people moving from private schools to public schools. It is seen as an economic reality and saying that you know, they just couldn’t pay the fees. And most private schools shut down because they are not as financially sustainable. But it will be great to get more colour on some of these, both the loss of learning outcomes and the shift to government schools across the country.

Rukmini: [00:37:59] So I think the shift to government schools, we have to watch and wait and see where the economic barometer is. And I’ve been reading with great interest, you know, other studies that are coming out. For example, I think there was a paper that Raghuram Rajan wrote recently that talked about luxury car sales being up. Middle-class sedan types are kind of steady, but the two Wheeler sales are down. Now, you know, I think some of these are correlates of a slower recovery perhaps in certain parts of our economy and so on. But I also think we should not underestimate what the government did during Covid because if you were in a government school across the board, we did a couple of phone surveys in that period because we had our sampling frame from 2018. We collect phone numbers from families because we do cross-check and verify. So we had a 2018 sampling frame that we could go back to. I think government school kids got textbooks, which private school kids did not. They often got rations. They had teachers who were, you know, still on the payroll. So they had many teachers reach out and so on. So I would say that the combination of that plus a big push on FLN which you can see in terms of materials, in terms of improvement. So there is not just a push. I think there may be partly a pull as well, but we have to wait and see, you know, to what extent this mirrors what kind of economic recovery or is it really a school being able to, you know, attract. Again if I go back to U.P., it is one of the states where learning did not fall.

Rukmini: [00:39:33] Why did it not fall? You know, ASER doesn’t have to have an answer. But a couple of years preceding, a lot of things have started happening in U.P. to shore up, you know, physical infrastructure, some big catch-up efforts, you know, various things. Whether it’s a push or pull on enrolment, we’ll have to wait and see. On the learning front, you know, at some level, I think Covid was you know what the right word is? It gave the right opportunity to talk about learning when people paid attention. If you look at the ten-year, 15-year stretch and if your eyesight is slightly bad and you see the ten-year graph from a distance, there are ups and downs, okay? And the Covid one is a slight down. So what people think, I don’t know to what extent they accepted the situation was very worrying before, Covid gave us an opportunity to talk about the Covid time, but also look back and say that we weren’t doing that well earlier. And so, you know, between 18 and 22, there are three periods, 18 to 20 when it was business as usual, 20 to almost 22 when business was completely not as usual. And then maybe a couple of months because last year we had long summer vacations because of the heat when you kind of came back. So the 18 to 22 difference is a mixture of all of this. If you look at Chhattisgarh, the Chhattisgarh government commissioned an ASER in 21 and they asked us to double the sample size because they wanted District level estimates.

Rukmini: [00:41:01] In Chhattisgarh, you see 18 to 20 big drops and 18 to 21, big drops. But, 21 to 22, an increase which is as large as the increase that they had managed to do in the six years previous. So again, you know, because the tool is simple because you can move fast, there is a lot of dynamism that is going on. Some of it you can’t see unless there is availability of it. One thing about 2022, I want to say, and this is I’m going to try this out on you and on your listeners, and if people don’t agree, they should write back to you. And you can tell me. If we look at grade three, standard three, the last ten years from 2012 till 2022 by and large for India, you can do the same for every state by and large for India and if I take ASER’s highest level in reading story level, which is a second-grade level text and if I take subtraction two digits subtraction with borrowing, which is again a second standard by and large in standard three, India has not gone beyond 50% in the last ten, which means that 70 plus per cent kids are left behind before you can mean in the first three years of school, which is a loss of potential here you can imagine. And it’s only that 30% or less that moves forward into the school system for which we are all turning ourselves backwards, helping them to do their exams well, get them into college, blah, blah, blah.

Rukmini: [00:42:24] So that’s the reality. So Nipun Bharat or FLN or whatever has to take this number, after Covid has gone below 25, right? But it was already around 27. I mean, it’s not like it was high. Anyway, we have to take it to the next five years to as close to 100 as we can. That’s one step. But if I look at this grade three a little bit more closely, the 2022 standard three does not look dramatically different from all the other standard threes, but behind it, all the other standard threes 12, 14, 16, and 18 had three years of schooling. In school being given by teachers and materials and whatnot. The 2022 Standard Three has had a few months of school. They should have been standard two in 21 and they should have been in class one in 20. They didn’t have that. So that 25% is actually what family and community have done. And the previous 27% is what schools can do now. I may be being very simplistic, but if I put the two together, people can be at 50%. We recognise that we are all players in the same game and we get our act together. We don’t keep parents out. We welcome them in and that’s one of the things that Covid has put to everybody. You know, parents are a big force in this and they’ve shown that they can do it. So I feel like the 2022 results should be looked at for the younger children as parental contribution, community contribution and older children as their own contribution or their sibling contribution.

Rathish: [00:43:56] I have four very meta-fundamental education questions for you after what you said but want to come to them later because I think the foundational literacy piece and the point you just made about and how to make foundational literacy work I think is an important point. I want to take that a little further and then maybe close with those four meta-questions. Even short answers from me will be great. One of my theories, ma’am, think that I’ve been now convinced about is it needs a set of compassionate adults around the child to make a child learn, which this is the story of my life, the story of my son’s life, which is that I can’t provide academic input all the time. My mom actually has only one eye. She never barely managed 10th standard, etc. But the fact that she sat every evening and made sure that I finished homework got me through education. And so I often wonder how we underestimate the value of compassionate adults at home who don’t have to be academically brilliant, but just the fact that they commit to the learning process of the child actually makes a big difference. And what you said sort of makes, you know, for me it resonates deeply. And as we look at Nipun Bharat and what we have to do and look at, having looked at the data over the years, what are some tangible recommendations that you would make that we should totally keep in mind, as many organisations have now started working on and given the government’s push on those areas.

Rukmini: [00:45:08] I mean as Pratham, I think our contribution to these early grades, early childhood, is to bring families in a big way. Remember that the mothers of children who are aged 3 to 8 are the beneficiaries of the Universalisation of elementary. They have years of schooling. They are savvier. And for a whole variety of reasons, India has very low female labour force participation, so they are tied to home. They have high aspirations for their children. They have greater capability for themselves. And therefore, at least in Pratham, everywhere, wherever we can operate, bringing mothers on board in a big way to engage directly with children’s learning is something that we are doing. And a second thing that we are doing, which is from observing what’s in our landscape, is that India has been very successful in structuring women’s groups, microfinance, and self-help groups. So that is also not a foreign formulation that women come together in their hamlet to do certain things. So I would say that these mothers’ groups and mothers’ engagement and not because fathers are not important, but often fathers are away for weeks or months or even the day. That is certainly that, you know, we must and, you know, I kind of even quantitatively feel like if you add what I was saying about grade three, it can have a huge piece. The second thing is we should recognise that in the past eight years, there has been slow progress.

Rukmini: [00:46:30] But if we need a huge big jump, you have to do things completely differently. Business as usual. Better training, better material, better, and stronger. You have to think, what is the big jump? So according to me, the big jump can bring the parents, and the teachers, put them together, a big jump or something else, right? Now the government, I think, recognises some of this. So the National Curriculum Framework for the Foundation Stage has been released quickly and if you go through it, it is a little bit different from what usually has been made. But I think with these instructional patterns, what is our business as usual? Instructional patterns have to be put aside. I was talking to a group of block-level people in U.P. U.P. is organising for example, they want 100 blocks to be NIPUN blocks sooner than the others. They are giving a lot of extra emphasis to these block teams, team building, motivation and so on. And I was talking to about 50-60 of them last week and I said that you know, frankly, the future of U.P. is in your hands because no matter what the frameworks are and what the materials are, they are hanging far up in the air. The teacher is a piece of all of this. She can’t unless every teacher becomes superbly enlightened and starts doing something totally different. But you have 20 schools, 15 schools under you.

Rukmini: [00:47:47] So, even then, it’s very simple. And what I said is what I do myself. So I can’t tell you to do something else that I don’t do. Every class I go to. I enjoy being with the kids. Do I learn something from them? Do I take that learning into the next class? Because kids can tell you a lot if you watch them closely. And so if you enjoy kids, if you see that the kids that you are interacting with are making progress, U.P. is all set. It doesn’t matter what is on the dashboard or what is not on the dashboard. Okay. This is why the entire interaction with children in learning in the classroom has to be different. Everyone has to feel that there is a different air and that we are on a different path. And so, you know, in some ways I feel like I hope that this realisation and that’s what the techno-managerial approach worries me because it’s a very top down. Take my 365-page manual and please do it every day properly. Well, no, because my every day is a hodgepodge. You know, tell me my goal that I have to reach in a month or in a fortnight and if I can’t do it, help me launch these things, you know, don’t see your numbers on the dashboard.

Rukmini: [00:48:55] Well, you know, too bad. I was busy with the kids. I think you need a and I feel like Manish Sisodia in his book. I hope he’s writing a second book. But one of the things he says is that no Shiksha needs to humanise the whole thing. Kids are human beings, they want to feel that they are making progress. When a kid makes progress, when you came first in your class or whatever you did, your mother felt that all our efforts were worth it. So, you know, and these little small things: a kid learning to read, a kid learning to swim, a kid learning to ride a bike. Everybody takes pleasure in it. So how do we bring in I mean, I don’t know, maybe you should convene a group of technical experts that we say, you know, do you enjoy being with kids in the classroom? If not, move out because the whole edifice needs to be built from there. And, you know, at that age, it’s so easy to have fun. You know, it’s much more difficult in Ninth Standard to have fun because now you have calculus and this, that and the other hanging over your head. Here it’s words and letters and stories and numbers, and they can fall from the sky. And it is the most fun age of all.

Rathish: [00:50:10] As you were talking, I was thinking that a happy child is an outcome everybody can stand behind. It is very hard. You might disagree on other things. Who has to come to power? Who has to win elections? But you can’t disagree with the idea that we need a happy child.

Rukmini: [00:50:23] Videos of these kids. You know, when we do this, learning to read or teaching at the right level, you take a video of a child who is beginning to read letters. They don’t and they are like eight years old. They don’t meet you in the eyes. Often we are looking here and there. By the time they are reading stories, the backbone is straight, the voice is clear, and the eyes are in your eyes. So it’s not only reading, it is self-confidence in myself that I can do it. And that self-confidence is very infectious for all the adults around to feel that you know, this is all worth it.

Rathish: [00:50:56] And this kid in a candy store now has so many questions. I have very limited time with you, so I’m going to ask you three questions. You can pick any one of them, go deeper or answer all these questions, but some of them are meta. One is, um, there is this large debate on should government-run schools should regulate education. Because the state capacity in this country to do everyday work is poor. Like I constantly when I work with civil service professionals recognise they can pull off the impossible very easily. But the everyday one, you know, the system sort of struggles in. So there is this constant debate on should the government actually just run schools at all or should just the government regulate education and do that really well or provide the funding. You’ve seen this now for over 20 years. And you know, when you talk about Covid and people moving to government schools, that was a question that came to my mind saying, what is this? You know, what should be the role of government in the long run? You know, maybe not this year, not next year, but over a period of time. That was one question. The second question that I was thinking about again, as you were talking, is whether we look at Covid and the short-term blip. But as you were speaking, you talked about how schools were closed because of air quality in Delhi, for example, there are schools getting closed because of floods.

Rathish: [00:51:58] And I constantly wonder if this conversation on the fact that disasters are becoming recurrent is part of our thinking around how we look at education. And we said something. It seems like an external factor, but is that something that we should think about? Saying that frequent school closures for many reasons, for floods, for, you know, air quality, etcetera, are going to happen more often, which sort of reinforces the role of the parent and the community because, you know, it’s not a one-time thing that’s going to happen. So this intersection of climate change and or climate change in general and education, is that something that you think needs more thought in the light of what we just discussed around parents and so on as well? I think that’s the other part. And the third thing, and you talked about U.P. right in the beginning and said we’ll come to it in the end. Are there things that state governments are doing that you feel is extremely good that you think should be replicated? You know, even in passing? You mentioned how U.P,’s numbers didn’t go down during Covid. You talked about what Chhattisgarh did. If there are examples of what states have done, which you think you can highlight and again, no limited time, that would be great. But those are the three questions I wanted to ask.

Rukmini: [00:53:00] So very quickly and I’m like that as well. I want to taste every candy that is there in the store. Rather than the role of government, how should we run? Our number one is one size fits all does not work in India. We have huge variations even within the same state. How can you have a framework for action that allows you to be flexible but decentralised? You know, why is there a distrust of decentralised, maybe decentralised or district level or block? I don’t know, some level at which if you give a goal and give an achievable goal, provide the resources, let people loose and have some kind of a way in which progress can be tracked in a constructive way. Now, private schools, if you control for, say, parental education, actually don’t do that well, at least in the large part of the low-cost private schools. It’s not like private schools are doing an amazing job or anything like that. What does it take to run schools that can achieve goals? What kind of support is needed? I think that is the critical thing to figure out. And, you know, you come across younger and very energetic district level people. And if you were to say don’t try this for all 600 or 700, say 100 districts, go for it. Let’s learn. I think we could learn. Disasters or school closures, people are now fixated on climate change and, you know, floods and so on. We have some very predictable education disasters. Elections are one, census is another one. These can be planned. These keep schools closed or keep schools at half mast for an extended period of time. Why do we have a year long? Why do you need to be in class three for a whole year? I’ve never understood. I mean, just because it’s a convenient thing and your school uniform can be made once a year or what? Because I think that even in a normal time there is a monsoon time, July to October, where often, you know, very heavy rain or floods happen. So Assam should not plan to achieve too much in that period because, you know, floods. Then there is a Diwali to Holi period, which is generally a good period as long as you don’t have elections in that time. I mean, if I want to write to the Parliament and say, Please can you have your elections in May and June, do it in the summer holidays, it’s a bit hot, but it doesn’t touch other people. Then the kids can have a full school year and it happens.

Rukmini: [00:55:09] So I think of two things. One is the predictable school closures or schools running at half mast can be planned better. We can have seasons you know, you can have units which mean, you know, fancy universities have quarters and semesters. Why does our school system have to have a whole year? You could have things which are you know so that if you miss one quarter is bad you know you need to get in, you know, so many quarters and so many years and you can accelerate a bit or something like that. And then that will take care of, you know, the automatic mechanism that gets into place when schools are closed for any period of time. And finally, I think that you know, I don’t know what state governments are doing and where can we replicate it, but certainly some things for example, this I think that this real welcoming of volunteers to help and more people need to try it and more people need to try it in a way that, for example, in Bihar, panchayats are taking charge and saying, the kids are ours and so are the schools you don’t give other people an opportunity to say, come on board. Right. And it can’t all be done through committees. And, you know, whatever task forces Maharashtra, for example, and I’m quoting the example, which I know because we have some work with them, there may be others which I don’t know because we are not working with them, has taken this mothers’ business on full-blown.

Rukmini: [00:56:23] Every government school in Maharashtra has mothers groups by Hamlet who do a whole period in the summer of school readiness. There are two Melas run by the means organised by the government, but run by the mothers. To say that by the time my child enters school after the summer holidays, my child will be ready alone. The whole breadth of skills and activities for those are being practised. And through the year these mothers’ groups are kept connected through, you know, virtual means, real means, whatever it may be. So I think there are these things, but you need to look at the effectiveness. You know, I may have a great idea and maybe try it out. But I also need to have something which says, you know, is it going according to what I want? Because engagement can be very heady, engagement leads to impacts of all kinds, including children’s learning. Time needs to be looked at closely, but in a simple way that can be shared and discussed and moved. You know, you move on.

Rathish: [00:57:20] I have so many more things I want to ask. Want to talk to you about social-emotional learning. I want to talk to you about technology and enabling parents. I want to talk. But ma’am, thank you so much. I think I always worry about reports because they abstract real people to numbers and then it becomes a statistic and the statistics become inhuman and that sort of gets dehumanised as it gets bandied about everywhere. But in today’s conversation, we made it about the child at the centre. I mean, for me, this image and again as a parent is very hard to not have that image of a happy child at the centre of everything we do, you know, the child that is sitting erect in meeting you in the eye and that’s the image around which so many people can come together. I often get asked why, despite so much money being spent on education, education is the Harry Potter of the social sector. Everybody loves it. Everybody puts money into it. Why don’t we get outcomes? And exactly today, what we discussed is whether we can decentralise and move it closer to the context rather than put a one size fits all model. Can we evoke constructive action from different parts of the community? Can we create more owners who own the problem than just a few people sitting in Delhi? Can we get mothers involved? Can we make sure that they recognise the value of the education they are getting? And all of these are super, you know, principles for us to approach this. It’s been a super valuable conversation. I really hope every entrepreneur and budding entrepreneur who is thinking about education is actually listening to this conversation. Because I think the point is education is not a technical problem. It’s a social problem. And I think that was extremely important for us to cover. Again, I know you’re very busy. Thank you so much for making the time. It’s such a pleasure talking to you.

Rukmini: [00:58:50] And I’m not that busy and hope to meet you again

Rathish: [00:59:00] Thank you, ma’am. Thank you so much.

Outro: Thank you for joining us here on Decoding Impact. We hope you enjoyed this episode and the conversation with our expert. To learn more about Sattva Knowledge Institute and our evidence-based insights, follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter and Instagram and explore our content on our website, all linked in the description.